Introduction

The quest for finding minimal superpermutations has a long and storied history. While proposed in the early 1990s, the problem remained dormant for nearly 2 decades. Then the problem was independently discussed on 4chan where progress was made and the lower bound was improved.

The task is, for a given , to find a minimal string that contains every permutation of elements as a substring. For example, for the string must contain the sequences and . By ordering these cleverly you can make the end of one permutation overlap with the beginning of the next. Here the superpermutation is - you can check to see that every permutation above appears somewhere in this sequence.

Articles about this seem to pop up once every few months or so, discussing how anime fans performed some leading math research (despite that not being strictly true).

However, I've never seen much discussion about the actual math involved in the problem and where the problem stands today. Some articles mention that the problem is still unsolved, but why? What is makes it so difficult? What are people working on? Did everyone just give up?

The Math

I'll try to describe a high-level overview of the math behind this problem. If you want a more in-depth look I cannot recommend this resource more highly.

The problem can be thought about as a graph. Let every permutation be a node and let there be directed edges with a weight equal to the amount of characters you have to append to the end of the first permutation to get to the second. For example, would have a weight of , since adding a to the end of creates the new permutation. But would have a weight of since you would have to add to the end.

Since we want to find a string with all of the permutations as substrings, we just need to make sure that we visit every node in the graph. Mathematically, we want to find the minimal Hamiltonian path of the graph.

We can create a graph with all these nodes and populate all these edges. The graph is symmetrical so we always start at node for simplicity. We can define a greedy algorithm that says to examine all the edges from our current node, from lowest cost to highest. Let's the first edge that takes us to a node that we haven't visited yet.

And it works!... for . People thought it worked for but there was another solution that was found that had 1 fewer character. And currently there's a solution for that gives a length 7 shorter than what this greedy algorithm would give.

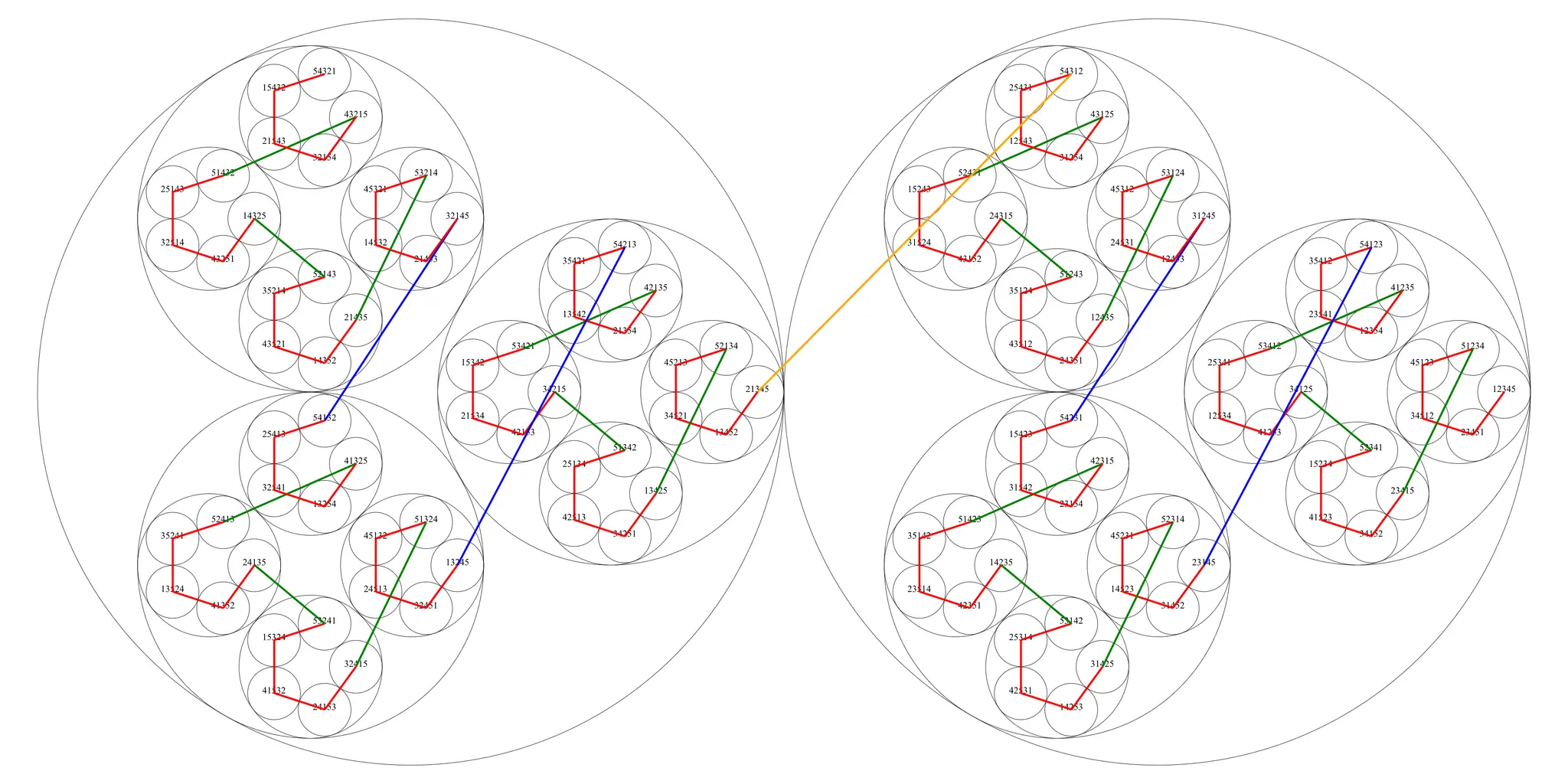

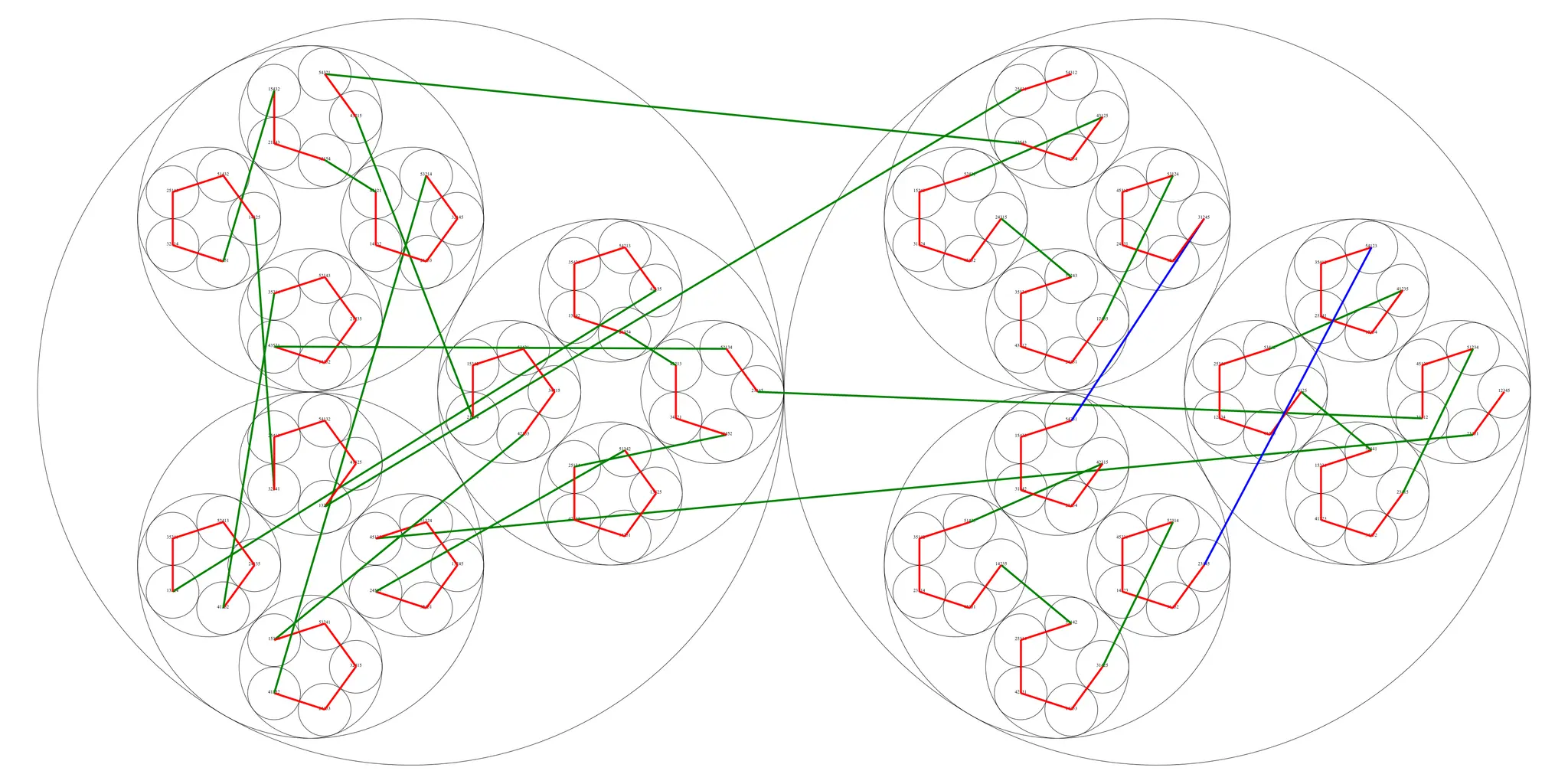

Essentially, by jumping around a bit and taking slightly longer paths at the beginning, you can avoid having to take those really long paths that you'll eventually be forced into when traveling along the greedy algorithm. When these can come out to the same value, but for it starts to pay off. These visualizations can help us understand what's going on.1

As stated, this is only the basics of the math involved here. There are other methods to generate better solutions that require more intensive graph theory. If curious, please read this page that I linked at the beginning of this section.

The History

This problem has seen occasional bursts of activity.

Cases for and are small enough to brute force - you can test every possible combination to ensure that there is no valid solution of a smaller length. These were known in 2011 by the 4chan investigators.

But then the puzzle was mostly untouched until 2013 when Nathaniel Johnston wrote about it. The following year Ben Chaffin discovered a clever algorithm to exhaustively show that the minimal length for was indeed 153, the length given by the greedy algorithm.

Inspired by recent events, Robin Houston would, later that month, show that bucks the trend - instead of the string of length 873 being minimal, as conjectured, a string of length 872 was provided.

But after this flurry of activity the puzzle was again left dormant until 2018, when Robin Houston created this GitHub repo and this Google Groups page.

Unfortunately, however, despite a lot of tooling improvements and some increased visibility, the only material improvement to come was the reduction of the case to , announced in the comments section of a YouTube video (explained here). Using that approach as inspiration, Robin Houston and Greg Egan had a large breakthrough and worked together to lower the case to later that month.

At a very high level this 'kernel theory'2 provides a pattern for describing the early 'jumps' that you can take to try to save on those later higher-weight edges. The 'kernel score' gives the length that the superpermutation would have if it exists. Formalizing this theory was very useful for quickly improving the case.

But this is the still the state of things today.

Stalled Progress

The lack of material progress isn't for a lack of trying. The problem is just really hard.

These permutation graphs are symmetrical and seem like they should be ideal to analyze, but in practice they feel messy and chaotic. Additionally, as the size of the graphs grow the search spaces become increasingly unpractical. It is for this reason that, despite it being almost certain that the current best solutions for and are not optimal, there has been almost no effort put into determining better solutions. The search would take a huge amount of compute.

Based on Houston's kernel theory it's possible that there is a shorter length superpermutation for . Unlike some of his previous theories, though, which described how to construct a superpermutation of a given length, this one is probabilistic, describing a structure that a solution might exist for. For finding the current solution of , 1.6 million kernels were generated and tested, 7 of which produced actual valid superpermutations3. It's hard to predict how long it would take to generate and test all the kernels that could result in lengths of , and even if they were all generated and searched there might not be any results.

Even the case hasn't seen a ton of progress. Despite there being at least discovered unique superpermutations with length 872,4 it's still unknown whether 872 is actually the minimal length. Though this also hasn't been for lack of effort.

One of the most interesting parts of this entire saga came in 2019 with the Distributed Chaffin Method search. Named after Ben Chaffin, the man who proved the result for , the idea behind the Distributed Chaffin Method was to take the same algorithm and allow it to be run concurrently across many servers. That way people could donate runtime to try to solve the case for . (This was created by Greg Egan. As far as I am aware Ben Chaffin had no involvement in this except for creating the initial algorithm in 2014.)

The search went on for over 4 years but was eventually cut short. After 100 million CPU hours the researchers realized that, at the current rate of computation, the answer wouldn't be reached until around, optimistically, 50 more years.5

There is a promising alternative for the case, though. In 2021 Cole Fritsch published both a paper showing that the smallest possible superpermutation for is length and a Python program showing that a superpermutation of length is impossible. In tandem, they effectively show that the minimal length superpermutation for is , matching the current conjecture. Cole Fritsch does, however, admit that the proof was not entirely complete and, in the paper, includes notes that certain sections need to be fixed. It hasn't been updated since 2021.

I have not had the time to study either. I'm sure there are some good ideas in the paper but, with an uneven interest in the problem, it has not been reviewed by many (any?) with formal mathematical training and has not been verified.

Overall, this list of current problems from 2019 is unfortunately still extremely relevant today. There has been relatively little work of any kind since 2021.

A Surprise?

After doing a bit of research into this topic I wanted to make a contribution, even if superficial. I loved this history of amateur mathematicians periodically making progress on this silly problem and it sounded fun to be a part of. And I thought I had identified the perfect opportunity.

Greg Egan provided all of the code that he used to find kernels and generate superpermutations on GitHub, and seemingly no effort whatsoever had been put into improving the case for . Any solution with a non-zero kernel score would be a new record. Some of these kernels have to be possible.

And there was a backup possibility with . A solution with a better kernel score could result in a solution of length or less. All kernels of length 35 or less were exhaustively searched, but the only thing stopping anyone from doing more was compute.

I cloned the repository and started running it on my home server, an M4 Mac mini. But unfortunately I quickly discovered that I completely misjudged the size of the problem.

You might believe that the time required to find a solution increased by somewhere in the realm of , the number of permutation with elements. This appears to be how much the 'size of the problem' grows by, and is approximately the size that the solution grows by. In terms of the graph, is the number of nodes.

But the number of highly relevant edges (edges of weight 1, 2, and 3, which can't be reached through a combination of smaller edges) is then (and nothing says that an optimal solution for these higher values wouldn't include weight 4 edges - that would bring the total to ( this is )).

When traversing through the graph to find a solution you can use techniques to prune some of these possibilities as you go. Naturally, when trying to minimize the total weight, you will need to take as many 1 weight edges as possible. But a standard Traveling Salesman approach would lead to a runtime of around - a far cry from 6. If the case for took me an hour to find, an increase in runtime could get me the solution in 8 hours. A increase in runtime would find the solution in hours. Probably should have done the math before I got the program running.

I have optimistically left the program searching for solutions for the past 2 weeks, but, as expected, it hasn't turned up anything.

Future Work

Currently the state-of-the-art revolves around kernels. This is likely where future research should be focused. Any breakthroughs around shaping these structures could lead to significant progress on the lower bounds.

Advances on the algorithmic/coding side could lead to new minimal superpermutation discoveries. From my little bit of testing I think there is room for improvement both in terms of kernel selection and in determining if a given kernel can produce any valid solutions.7 The runtimes of the searching programs could possibly be improved as well.

I wish I had more time right now to review the code and dive more deeply into kernel construction.

But for anyone reading, let this be a gateway with resources that you can look into if you want to get started. And hopefully if I do find the time I can review this to jump back in.

The search for minimal superpermutations is not over. But whether the next one will be found in 1, 5, or 10 years... well, that could be up to you!

Footnotes

-

Full credit for the structure behind these visualizations goes to Greg Egan as published here. The ones on this page were generated by this code that you can find on my GitHub. The circles represent 1-, 2-, ..., -cycles that are defined by the greedy algorithm (there are other ways to generate 2-cycles and higher order cycles in these graphs). I wanted to explore this visualization method more because it preserves the 1-cycles so nicely but by it becomes too chaotic to make much of it. Even the non-greedy case above shows the limits of this method. ↩

-

While this idea was first put into practice by Bogdan Coanda, the person who discovered the 5907 length sequence, it was further refined and expanded on by Houston here. ↩

-

I repeated a portion of the same test that Egan initially performed to find the superpermutations of length 5906 on my M4 Mac mini (described here as Search 1). The kernel generation took a few minutes. Checking these kernels took about an hour or 2 to find a valid solution. I had to cut this test short because of some system configuration issues, but I would expect that the exhaustive search to rediscover all 83 of the solutions he found would likely have taken around a day or 2 based on the rate it was processing. I should also note that it is fairly trivial to parallelize this process - distributing the checking across 6 cores (a conservative limit on a 10-core system) would speed up this process by a factor of 6, and all 83 solutions could likely be generated within 12 hours. ↩

-

My understanding is that this is the number of solutions of a particular structure, but that solutions of other structures exist for . ↩

-

For a detailed description of The Chaffin Method you can read here. At a high level it checks to see if any solutions are possible for a set number of 'wasted' characters, wasted characters being ones that don't immediately create a new solution. It is expected that the case for will have 147 wasted characters. The network spent over 1.5 years trying to solve the case, and generally each additional case takes longer to solve. 25 more cases at an increasing growth rate would take well over 50 years. ↩

-

I haven't even had the time to dive deeply into Egan's code to see how the search is implemented. I don't have an estimate for it's runtime as written, but it's safe to say it's in between the two. ↩

-

For example, I have noticed that all palindromic kernels with an odd number of symbols are unviable and can be excluded very quickly - but is there a way to prove that no solution of this form can exist? Can other large classes be excluded? Searching would see significant speed-up if we can improve at ruling out large search spaces. ↩